The new transcendentalisms

Hi folks,

The last newsletter was about the ways we pay for everything with our attention. This one is about freemasons and transcendentalists and P.T. Barnum. I think these things are related! The web these days is one long caravan of spectacles and scams, and so is the entire sweep of American history.

Maybe you’ve noticed how often we use metaphors drawn from 19th-century Americana to explain contemporary internet culture. We talk about platform monopolies ushering in a “new gilded age.” Crypto is either the new gold rush or the new Wild West, depending on who you ask. Even “fake news” recalls a time when media bent more willingly to the whims of the robber barons.

I think there’s something more than correspondence in these tropes, which is to say, I’m interested in how we might understand the internet differently if we pushed back the so-called “rise of the networked society” by a hundred years or more. Maybe if we paid closer attention to the socialities, spiritualities, movements, publications, and literary discourses of the 19th century, we’d find pre-digital networks that link up with our own.

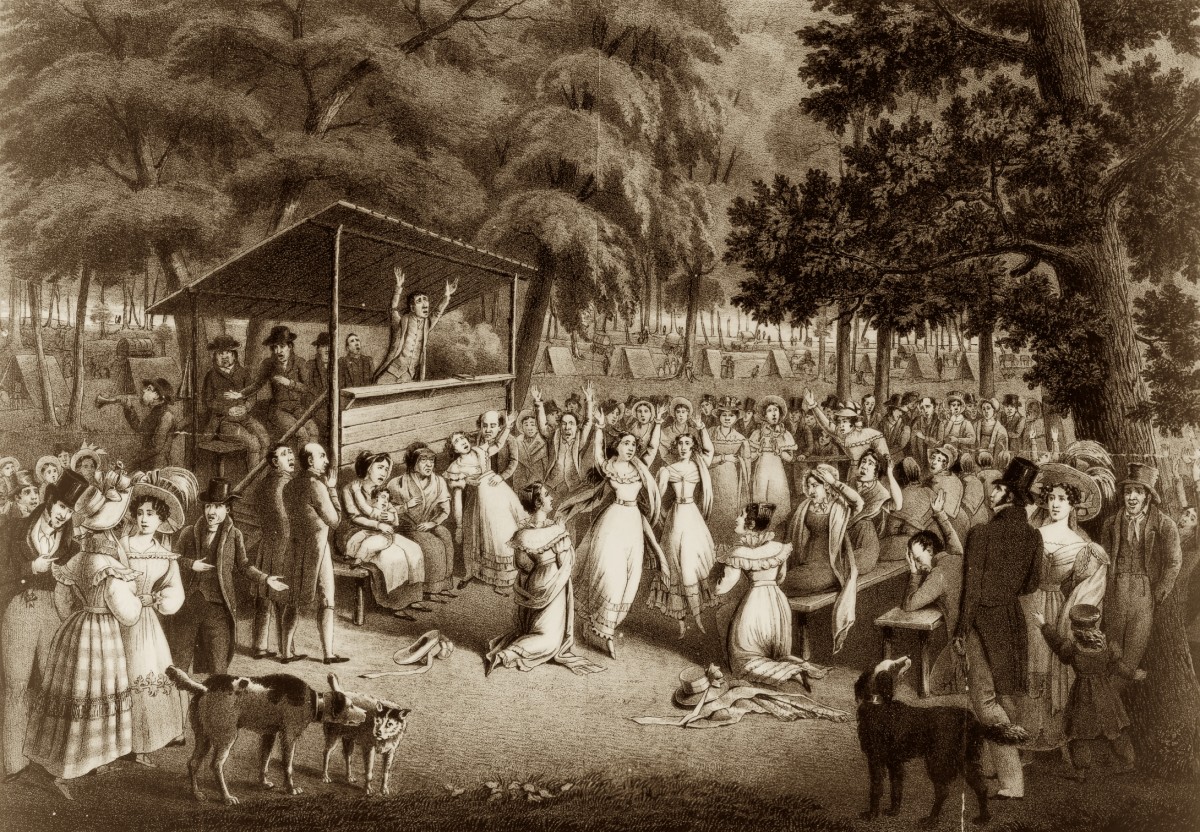

An early 1800s camp meeting, lithograph of unknown origin

Grifters!

Anyone who read Tom Sawyer in grade school sensed that scamming is a deep-seated element of American psychology. People like Anna Delvey and Billy MacFarland and Elizabeth Holmes are merely the latest in a long tradition of hucksters and cheats who went on to become national sensations. As Jia Tolentino wrote in 2018: “Grifter season comes irregularly, but it comes often in America, which is built around mythologies of profit and reinvention and spectacular ascent.”

For Tolentino, who hones in on our sympathetic fascination with scammers, the hoax has a way of both deflating and reanimating that other quintessentially American myth – the up-by-your-bootstraps meritocracy our politicians and capitalists love to profess. On one hand, we can all see the system is rigged, so why not root for those with the gall to game it? On the other hand, aren’t all of us on social media basically scheming to capture other people’s attention?

Maybe the recurrence of grifter season follows the spooky pendulum of financial crisis. Maybe it’s astrological. For the New York Times critic Amanda Hess, grifter season is simply what you get when the Silicon Valley “entrepreneurial fetish” saturates an online economy built around immersive media and user engagement. “In this hyper-visual culture,” she writes, “constructing an image of something can feel like the most important step in conjuring the thing itself.” Reading that made me wish more people were situating today’s grifters in a longer window of cultural history and media ecology. You don’t have to look far for a sense of the similar hysteria which was pervasive in the postbellum United States. Mark Twain, for example, got famous with a hoax story, squandered millions on what today we’d call angel investments, and spent his later years traveling the world giving the equivalent of TED talks.

Last year I stumbled across a book called The Stammering Century, which does exactly this. Published in 1922, it’s a compilation of hot takes by a New York literary critic named Gilbert Seldes who spends 300 pages skewering the utopian fanatics and wheeler-dealers of the early U.S. Here’s how he sums it up:

“[This book’s] personages are fanatics, and radicals, and mountebanks. Its intention is to connect these secondary movements and figures with the primary forces of the century, and to supply a background in American history for the Prohibitionists and the Pentecostalists; the diet-faddists and the dealers in mail-order Personality; the play censors and the Fundamentalists; the free-lovers and eugenists; the cranks and possibly the saints. Sects, cults, manias, movements, fads, religious excitements, and the relation of each of these to the others and to the orderly progress of America are the subject.”

I bring up this odd book because even though it reaches back to early days of the United States, it feels like it’s about today’s internet. Its interest in subcultural media reminds me of Angela Nagle’s Kill All Normies. Its soapbox personalities spread the same kind of memes and moral panics that pop up on Buzzfeed. Seldes talks about religious revivalists the same way that Twitter pundits talk about Alex Jones. Everyone everywhere seems to be searching for meaning in the emergence of mass media, the boom and bust of industrial economy, and the growing pains of national institutions – the same kinds of destabilizations we turn to the social web to address in the Trump era.

Left: the replica of Thoreau’s cabin at Walden Pond (photo byFlickr user Namlhots). Right: a Pinterest-ready reinterpretation in Pennsylvania.

New Transcendentalisms

A lot of the affective qualities of 19th-century spiritual and literary circles feel like they’re present today on YouTube, Instagram and Tumblr, where communities crop up easily around aesthetics, fandom, lifestyle, belief, and identity.

I almost want to call these groups “neo-transcendental” because they focus earnestly on recovering a spiritual connection with the self and the outside world. Like Thoreau’s Walden, much of their content is diaristic or instructional, and it ranges in scope from daily practices to broad philosophies. It often deals with the routines of inhabiting a body and making a home. Veganism, yoga, digital nomadism, minimalism, tiny houses, van life, nutrition, hygge, permaculture, and polyamory are all interest nodes for groups that communicate in this register around what it means to “live deliberately.”

There’s a connection to the commercial side of the Romantic world here, too. Content creators like vloggers need to monetize their audiences in much the same way that 19th-century spiritualists, reformers, and inventors sustained themselves through writings and appearances. This thread casting Thoreau as the perfect millennial gets at the similarity: “Participates in gig economy. Is an OK farmer for exactly one year. Most accurate job title is ‘Influencer’.”

The figure of the “influencer” implies a network of causation that’s traceable through a social graph. 19th-century literary and spiritual movements also spent a lot of effort trying to manifest this kind of impact. The Stammering Century is full of preachers and commune-builders who traversed lecture halls, newspapers, and other social spaces across the early United States making the case for their communities. Though they didn’t have digital communications tools, their astute marketing did give them a kind of virtual presence in popular culture – just like the real Fyre Fest wasn’t the event itself but the millions of people watching documentaries and snarking on the TL. I think this is something the Transcendentalists understood implicitly: utopian experiments like Brook Farm and Fruitlands were just as catastrophic, but did a lot to dramatize their image in popular literary culture.

“Fraternal” Organizations

Last week Venkatesh Rao tweeted, “We’re gonna see a new institutional underground of reimagined secret societies, lodges, fraternities, sororities etc.” Which makes sense! Trade unions, immigrant mutual aid groups, and other societies offered cohesion in the face of alienation. Though they sound musty and mysterious today, fraternal orders provided a highly coded social space where 19th-century men made professional connections, organized mutual aid, and conducted politics. (Some orders, like the Odd Fellows and their counterparts the Rebekahs, maintained separate affiliations for men and women). More formal than the so-called “third space” of cafe culture, this participatory structure outside the home is not unlike what the co-working industry provides for lonely freelancers.

It’s interesting to watch how this history flows into new contexts created by technology and real estate. Though Freemasonry was a global institution, it remained a quasi-private sphere largely outside the marketplace. Firms like WeWork and The Wing also build group identification through things like exclusivity, iconograpy, and networking, but the result is a subscription service rather than a social body. Their mechanisms of social reproduction are also public commodities.

With its “WeLive” spaces, the We Company is drawing on the even more integral experience of the commune (or kibbutz, in its Israeli founder’s words) to achieve a complete financialization of private life. The Wing’s #girlboss makeover of the fraternal institution shreds the historical separation between the public sphere and the feminized domestic one – though it also erases many of the more solidaristic structures in which women cooperated to influence public life since the era of “republican motherhood.” Even online white supremacists channel the history of secretive association left over from these groups – which were exclusively male spaces and overlapped in many places with terrorist vigilante groups like the Klan. This is all very crazy to me, and worth thinking more about.

History and metaphor

There are a lot more examples like the ones above. I’d argue the current turn toward astrology, wellness and self-care resonates deeply with the blurring of healing practices and spiritualism that took place alongside the formalization of medicine. On a darker note, the communicative register of the alt-right bears a direct connection to the violent white supremacy that spread virally throughout the 19th century and had its roots in even earlier forms of folk politics.

I think it makes sense to refer to institutions like the print newspaper, the fraternal organization, or the utopian commune as pre-digital network technologies which formed collective identity and coordinated both belief and action. To draw on Shannon Mattern’s history of the hardware store as a “social infrastructure,” these connective spaces “gave shape to the community” in ways that in ways remain familiar from our online interactions today. Sometimes even the terminology lines up: Methodist preachers in the West were known as “circuit riders” because the church dispatched them on horseback to rural communities, rerouting them dynamically across a vast territory like packets over a network.

But how do we dig into this kind of network history without simply bending the past to fit our present worldview? My friend Toph said recently in an interview, “it is striking how in the history of technology, in an age of hydraulics people see the body as regulated by fluid humors and the equilibrium among them. Or in an age of machines it gives you the gears and mechanical. And in our modern information age, we view it as code or computation or information processing. But from the broader historical perspective, when you see how every age projects its technological advancements onto its metaphors for itself, it’s not clear we’ve escaped those metaphors towards any kind of transcendent whole truth.”

In other words, to say “the Great Awakening was a social network” is to make one of those Gladwellian simplifications that’s more of a crutch than a thinking tool. When you look back in time you’re dealing not only with many kinds of “technologies” (each with their own lifespan and affordances), but also with ideologies, communities (imagined or otherwise), and discourses. These things are always influencing each other in unique and unpredictable ways.

I don’t really have a good answer for navigating all this, but I’ve found a good example in “Bunk” by Kevin Young, which traces “the rise of hoaxes, humbug, plagiarists, phonies, post-facts, and fake news” from Barnum’s circus through the Trump administration. Instead of playing a matching game between past and present, Young takes a multiply networked society as a given and digs into the interactions between new media and longstanding ideological formations like whiteness and scientific racism. He’ll zoom in on the cultural politics of individual deceptions, like spirit photography, but also pull way out to dissect broad cultural dynamics, like the Romantic mindset “in which pseudoscience and pseudospirituality got spliced together with the reactionary eugenics of Europe and America.” Throughout the text he pays close attention to the particular orientations of individuals, from Edgar Allen Poe to Rachel Dolezal.

I’m sure that fifty years from now our experience of the world will be mediated through new kinds of interfaces whose antecedents are only vaguely apparent to us now. I suppose what will create a useful sense of the past in the present is not a uniform set of historical references, but a quality of observation that remains alive to the multiplicities, consistencies, and contingencies in social experience. “Of hoaxes,” Young writes, “there’s never a shortage—but it’s also true that the weather of a particular time and place can influence what grows in a drought of facts. It is that weather the hoax measures.”

Thanks for reading!

In infinite expectation of the dawn,

Leo